The Case for Dependency Injection Containers

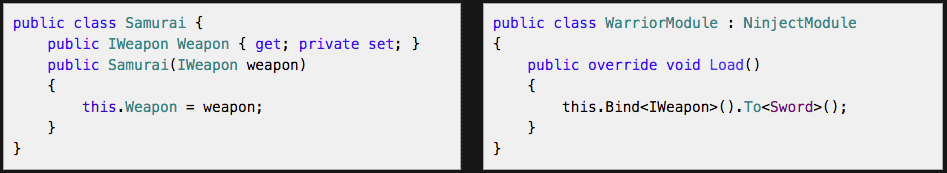

Ninject, one of the most popular dependency injection (DI) containers for .NET, introduces their tool with the following.

Source: www.ninject.org

The power, flexibility, and benefit of writing code like this may not be immediately obvious, and I hope to flesh out what containerizing dependency injections has to offer. We will not cover in depth advanced features of various dependency injection containers or their implementation but rather present an introduction why a software developer would and should use them. While the examples here may use C#/Java syntax, the object oriented considerations should be clear.

Good Object Oriented Principles

Let’s start with some good object oriented principles. Most applications have many features and do many things, so the object oriented (OO) code of an application are broken up into different objects in order to observe the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

Single Responsibility Principle: Each component or module should be responsible for only a specific feature or functionality, or aggregation of cohesive functionality.

— Microsoft Application Architecture Guide

Even objects that manage one of the application’s features often have many concerns (e.g. communicate over the network, update local data, render to the interface, etc), so in order to abide by the SRP, an object (the dependent) are composed by multiple objects (the dependencies).

One responsibility that may be easy to overlook is object construction. Constructing an object is a responsibility, so if an object constructs another object, it has used up it quota of responsibilities (reminder: the quota is one).

The Problem

Let’s look at a (contrived) example of how a Samurai object that takes on the responsibility of constructing an object along with its samurai related responsibilities, how the problem may develop, and how we might improve upon it.

// SS v0.1

class Samurai

{

ISword Sword;

Samurai()

{

Sword = new Sword();

}

}So far, not so bad. The default constructor for a Sword is sufficient for the Samurai class in Samurai Simulator v0.1 (SS v0.1). Let’s look at what happens when swords can now be constructed with different hilts.

// SS v0.2

class Samurai

{

ISword Sword;

Samurai()

{

Sword = new Sword(new Hilt());

}

}Still looks manageable. Now let’s introduce a cross cutting concern that will span many parts of our application. The cross cutting concern for our (still-contrived) example is the alloy that makes up the sword and hilt.

Now when multiple dependencies use an Alloy, the team asks who should construct the Alloy. Should it be the Samurai? The Hilt? The Sword? How would the alloy type be chosen? In SS v0.3, swords and hilts used by the samurai are made of the same alloy, so the engineers decided to construct the Alloy in the Samurai so that the same alloy can be injected into the Hilt and the Sword.

// SS v0.3

class Samurai

{

ISword Sword;

Samurai()

{

IAlloy alloy = new Alloy();

Sword = new Sword(new Hilt(alloy), alloy);

}

}This is where things start getting out of hand. SS v0.4 will have Swords made of different Alloys than their Hilts, so the same, previous discussion comes up (Who should construct the alloy? The Samurai? The Hilt? The Sword?), but is much more contentious now. Previous design decisions are re-examined, e.g. maybe the Sword should construct the Hilt rather than the Samurai. The team explores the implications of different design choices, and these design discussions take time. The implementations also take time because small logical changes cause cascading code changes, and future changes take time to design and discuss as the architectural complexity grows exponentially with each new dependency.

Possible Solution

Just as the readability of good code is based partly on its predictability, the extensibility of good architecture is based on the predictability of its evolution. The more predictable the code, the more an engineer can accurately predict and reason about the code with limited exposure to the code in the system. The more predictable the evolution, the more an engineer can accurately predict how the solution will evolve based on changing requirements.

Had Samurai Simulator adopted an Dependency Injection (DI) container, the container for Samurai Simulator could have evolved like this (the following examples use the Ninject API):

SSv0.1 - samurais have swords, all swords are the same

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();SSv0.2 - swords have hilts, all hilts are the same

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();

Bind<IHilt>().To<Hilt>();SSv0.3 - swords and hilts are made up of the same alloy

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();

Bind<IHilt>().To<Hilt>();

Bind<IAlloy>().To<Alloy>();SSv0.4 - swords and hilts have different alloys

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();

Bind<IHilt>().To<Hilt>();

Bind<IAlloy>().To<SwordAlloy>().WhenInjectedInto<ISword>();

Bind<IAlloy>().To<HiltAlloy>().WhenInjectedInto<IHilt>();SSv0.5-alpha pre-release - introduces ninjas who act a lot like samurai, no changes in injection module needed (refer to the SSv0.4 ninject example)

SSv0.5 - weapon system for ninjas and samuari will evolve separately; after some refactoring, we get the following

Bind<ISword>().To<SamuraiSword>().WhenInjectedInto<Samurai>();

Bind<ISword>().To<NinjaSword>().WhenInjectedInto<Ninja>();

Bind<IHilt>().To<Hilt>(); // hilts for all swords remain the same

// ninja and samurai swords share the same types of alloys, for now!

Bind<IAlloy>().To<SwordAlloy>().WhenInjectedInto<ISword>();

Bind<IAlloy>().To<HiltAlloy>().WhenInjectedInto<IHilt>();Product roadmap (left as an exercise to the reader):

- SSv0.6 - new weapon characteristics for samurais and ninjas

- SSv0.7 - dual wielding samurai

- SSv0.8 - multiple weapon types, combatants now wield multiple weapon types, including shurikens, spears, and rocket artillery, and at the same time

Conclusion

We observe that the implementation of each change in Samurai Simulator is much more predictable with an DI container than without. An engineer could have reasoned that the construction of every object that needs to be constructed would go into the configuration of the DI container. From there, such an engineer could design, reason, and predict a few possible elegant DI configurations that fulfill the requirements. The readability and maintainability also improves as each class is de-coupled from the construction of their dependencies, and the dependency construction/injection is more cohesively organized.

Even if this example is a little contrived, you can replace Samurai with some object that manages some role FooBar that foos some bars. Instead of the Sword and Hilt dependencies, FooBar uses the BarFinder and FooDetector dependencies. Instead of an Alloy cross cutting concern, we have an application-wide CacheManager.

Pros

Removes boilerplate code

When every class need the same logger/cache/barfoo, we define that binding in one place for every logger/cache/barfoo needed by every class.

Predictable evolution

When some category of objects now need a shared subclass of logger/cache/barfoo that is different from the original type of logger/cache/barfoo binding, all those dependency bindings were located in one place, so we make all the (hopefully minimal) changes in one place (yay SRP).

Cons

Another abstraction to learn

Abstractions can come at a high cost to learn, understand, and apply. Not understanding the containerization of dependency injection will make solutions that use DI containers hard to understand and extend elegantly.

Disciplined engineering still required

While DI containers can be powerful, that power can burn the team without a well-designed OO application to accompany the DI container as well as a well-organized DI configuration.

Multiple DI container solutions to choose from

There are potentially multiple approaches and subtle differences between DI containers to learn, although they should all have the power demonstrated so far using Ninject albeit with differences mostly due to syntax

Bonuses

Lifecycle management

DI containers like Ninject can also manage object lifetimes. Should the instance of a type start living in a Singleton scope? Add InSingletonScope() to the binding.

We start that every samurai should get their own sword.

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();This is all we have to do if we want every samurai to start sharing the same sword.

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>().InSingletonScope();Did that turn out to be a terrible idea? Let’s give all samurai get their own sword again.

Bind<ISword>().To<Sword>();Developers can use Ninject to just as easily manage the life cycles of objects to be based on thread scope or request scope (request scope applicable to server applications) or a custom defined scope.

Contextual binding

With great power comes great responsibility. And Ninject also grants the power of contextual binding. This was demonstrated when some swords (e.g. NinjaSword) were contextually bound to a particular scope which was the type of parent (e.g. Ninja). Ninject can give you many means to define the scope based on the context. The context can include attributes of the dependent parent, the attributes of the target, the name of the variable being injected into, and many other ways that are pretty well documented.

Bindings based on type are the most common and easiest to reason about since DI (and much of object oriented design) revolve around the ideas of types and concrete implementations. The power exposed by contextual binding extends beyond just type bindings, and like many other powerful features, they require disciplined execution to avoid creating a mess.

comments powered by Disqus